The consensus problem in distributes system is an age old problem. A strong form of consensus problem can be defined as follows:

Given a set of processors, each with an initial value:

- All non-faulty processes eventually decide on a value

- All processes that decide do so on the same value

- The value that has been decided must have proposed by some process

These three properties are referred to as termination, agreement and validity. Any algorithm that has these three properties can be said to solve the consensus problem.

Now these faulty processors can have 2 types of faults.

- Crash faults - Where faulty processes just stop. They don't act any further.

- Byzantine faults - In this case, we don't assume any thing about the faulty processes. These processes can behave aribitrarily. They can send wrong message, correct message to some and false message to some, lying, deceiving, anything is fair game.

If the processes only have crash faults, then achieving consensus is relatively easy. We can be sure that all messages we get are from correct processes as the processes which are faulty don't send any messages. Systems which only tolerate crash faults can operate via simple majority rule, and therefore typically tolerate simultaneous failure of up to half of the system. If the number of failures the system can tolerate is f, such systems must have at least 2f + 1 processes [1].

While if the processes can be Byzantine, they can send incorrect messages or correct messages to some and incorrect messages to others.Byzantine nodes are special in the sense that they can do any arbitrary thing (lie, deceive, etc). This lack of any assumptions about the nodes is very powerful and this is the reason why this problem is so interesting.

For solving for consensus in presence of crash faults, simpler algorithms like Raft and Paxos work. But these algorithms don't work in presence of Byzantine faults.

The problem of consensus with Byzantine Faults is discussed in Leslie Lamport's paper on Byzantine General's Problem. A solution for this was also proposed by Lamport, a good discussion about which can be seen here.

The problem with this algorithm is that it's a very costly algorithm. Leslie Lamport's solution to Byzantine General Problem requires O(nm+1) message transmissions where n is the total number of nodes and m is the number of byzantine nodes such that n>3m.

Practical Byznatine Fault Tolerance

Practical BFT is a consensus algorithm proposed by Castro and Liskov which solves Byzantine General's Problem in a more efficient way. Practical BFT requires O(n2) messages to achieve consensus in presence of Byzantine processes.

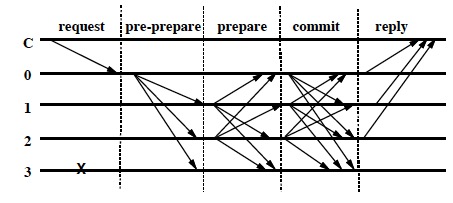

pBFT involves 3 stages in normal case operation

- Pre-prepare

- Prepare

- Commit

Fig 2. Normal case operation of pBFT

Fig 2. Normal case operation of pBFT

pBFT algorithm (as described in the original paper) solves for consensus in case of classic distributed systems. Though this has been adapted for blockchain based systems like in case of Hyperledger Fabric and Tendermint.

One important thing to keep in mind is that pBFT based consensus works only in case of permissioned networks - where the identity of nodes is known. Anyone can't just join these network. The operation of the algorithm is based on the identity of nodes being known.

Blockchain helps in achieveing consensus in distributed systems as it groups transactions in blocks in order to amortize the high commit latency (on the order of ten minutes) over many transactions. Also, linking blocks via cryptographic hashes into an immutable chain, makes it easy to verify the historical record (via Merkle proofs).

More in section 3.3 of this thesis.

In next section we will talk about Tendermint in more detail.

Tendermint

Tendermint was one of the first consensus algorithms to adapt pBFT for blockchains. Tedermint consensus algorithm is used by Cosmos Network.

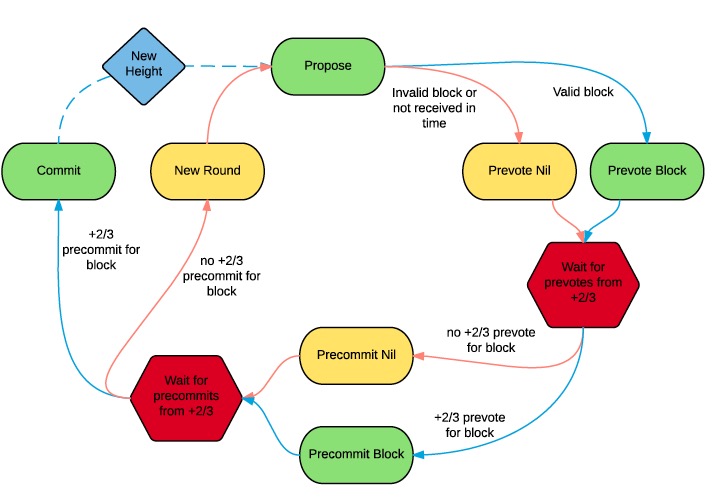

Fig 1. Basic description of Tendermint protocol

Fig 1. Basic description of Tendermint protocol

Tendermint involves 3 stages

- Propose

- Prevote

- Pre-commit

Once the above steps are done then the network moves to commit stage.

Why does pBFT need 3 steps?

Similar reasons as need for 3 stage for Tendermint explained below

Why is a commit stage needed in pBFT? StackExchange Thread

Why a 3 step protocol is needed in Tindermint?

A single stage of voting allows validators to tell each other what they know about the proposal. But to tolerate Byzantine faults (which amounts, essentially to lies, fraud, deceit, etc.), they must also tell each other what they know about what other validators have professed to know about the proposal. In other words, a second stage ensures that enough validators witnessed the result of the first stage.

As the primary can be byzantine, it may not send the request m to some of the honest nodes and the nodes in that case will not reply. But in that case, 2f+1 votes will not be obtained? - Or f faulty nodes and f+1 honest nodes vote for the message.

Why is a primary needed in pBFT?

Primary comes in handy to arbitrate the order of requests (Miguel Castro's talk - link in reference)

Leaderless Consensus Systems

Paxos proposes a consensus system without a leader, but it is more complex than a leader based system. So, key reason for having a leader based consensus system is the relative simplicity of design and reasoning about the consensus system.

Tendermint vs pBFT Reddit Discussion

- Tendermint executes one consensus instance at a time (in PBFT there are several parallel instances), as this is more appropriate in the context of blockchain systems.

- Tendermint (similar to Raft) has simplicity as one of key design decisions. There is no difference between normal case and view change phase.

- Tendermint is optimised for gossip based communication and is designed for high number of nodes (hundreds). Messages in Tendermint are of constant size and does not depend on system size, contrary to PBFT View-Change message that contains 2f+1 signed Prepare messages and that depends on system size.

Tendermint vs Casper Reddit Discussion

Tendermint was a bonded proof-of-stake specification before Casper.

One major reason why Ethereum didn't adopt Tendermint as its PoS was because Tendermint would halt when >= 1/3 of the voting power disappears. Tendermint favored consistency while Casper was designed to favor availability in case of network partition (CAP theorem) and that was the original point of philosophical departure.

Designing Fault Tolerant systems

When designing fault tolerant systems, 3 key properties should be kept in mind (Stackexchange Thread)

1. Crash or byzantine failures

Should the system be designed to withstand nodes just stopping to do anything (i.e. no messages at all) or should it also consider nodes which exhibit arbitrary behaviour?

2. Eventual or strong consistency

Should the system provide certainty, that some state is final and not revertible or are we okay with irreversibility with high probability?

3. Open or closed membership

Is it known in advance (and to all nodes) who is participating in the protocol? E.g. a reliable database used by google has a defined number of nodes, which are known to all other nodes. In Bitcoin it is unclear even how many miners are participating in the consensus algorithm.

For the most well known consensus algorithms, the properties are:

Bitcoin / Ethereum: Byzantine failures, eventual consistency, open membership RAFT / Paxos: Crash failures, strong consistency, closed membership PBFT / Zyzzyva: Byzantine failures, strong consistency, closed membership

Now there are two basic results in distributed systems which determine the trade-offs for a consensus system. These are CAP theorem and FLP Impossibility.

Otherwise called ‘Brewer’s Theorem,’ CAP theorem states the impossibility of simultaneously satisfying more than 2 out of 3 guarantees in a distributed system: consistency, availability, and partition tolerance.

Facing DDoS, Tendermint stops

The FLP result shows that in an asynchronous setting, where only one processor might crash, there is no distributed algorithm that solves the consensus problem.

References

- Miguel Castro explaining pBFT

a. Practical consensus (without Byzantine nodes)

b. pBFT (with Byzantine nodes)